Editor’s note: To honor the wishes of Soldierstone’s creator, The American Legion Magazine will not release specific information related to the memorial's location.

In a vast, open field at 10,000 feet of elevation in the 1.8-million-acre Rio Grande National Forest stands a mysterious war memorial called Soldierstone.

Winding dirt and gravel roads leading to it are often blocked by snow or floods even in the summer. When roads are passable, travelers find the terrain challenging yet serene. The nearest ranger station is about 15 miles away, on the edge of a small Colorado town where two diners and a gas station are the only shopping options.

Given the memorial’s remote location, it’s no surprise that few people visit Soldierstone. In fact, it is more common for cattle to be grazing in the field than for people to be gazing at the memorial.

Visitors who do make it to the memorial often leave tributes: U.S. flags, campaign service medals, spent shell casings, coins and more.

Claire Veech, commander of American Legion Post 54 in Gunnison, Colo., says he usually leaves a .308 shell casing when he visits. “It’s more or less to signify to the guys, here’s ammo. ‘You are still fighting.’”

Veech accompanies veterans and others who are curious. “When I first heard about it, Soldierstone meant nothing to me,” says Veech, who was a Blue Water sailor during the Vietnam War. “Since I have been here maybe a dozen times, it means more. Most veterans I bring up are pretty impressed.”

THE MAN BEHIND THE MEMORIAL

Soldierstone’s history is largely secret and its meaning often misinterpreted.

Stuart Allen Beckley, a retired Army lieutenant colonel and Vietnam veteran, was the visionary, architect and fundraiser for Soldierstone. His sister, Phyllis Roy, says he trained troops in Thailand and worked with armies in Vietnam, Korea, Cambodia and Laos.

One selfless act of courage propelled Beckley to make it his mission in life to honor those who assisted U.S. troops.

“He was impressed with a 10-year-old boy who had both legs blown off and crawled to the post to give a message to the Americans, which saved their lives,” Roy remembers. “That experience just really impressed him so much – that so many people gave their lives, or jeopardized their lives. He just felt that they should be recognized.”

RELATED VIDEO:

Tucked away in the Rio Grande National Forest is Soldierstone, a memorial honoring the nations and peoples who helped the U.S. during the Vietnam War.

Beckley clung to those memories while he spent a couple of years surveying the Continental Divide for the perfect spot for Soldierstone. He focused on finding a secretive location so the memorial would be shielded from vandals. He wanted to find “a remote place where people who should be looking at it would have access, but not in a place where anybody could tear it apart,” Roy says. “He was concerned about people destroying it because Vietnam was such a sticky war.”

Beckley spent 20 years and tens of thousands of dollars planning, designing and erecting the memorial. “He did everything for this memorial except physically construct it,” Roy says. “He wanted to pay tribute to the French Legionnaires, U.S. allies in Southeast Asia and private citizens who helped the Americans.”

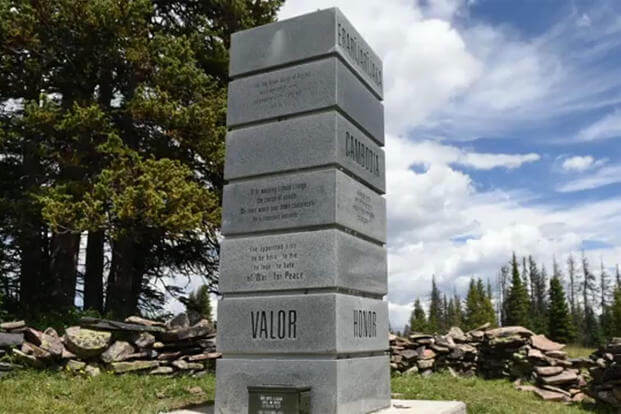

The final design shows painstaking precision and heartfelt devotion. At the memorial’s center is a 10-foot-tall monument with stone tablets on all four sides, surrounded by a triangular rock wall that suggests an abandoned outpost from Southeast Asia. Outside the wall are 36 300-pound granite stones in three concentric circles, representing soldiers defending the base. Each of the 36 stones contains quotes in languages of the Americans’ allies: Vietnamese, French, Laotian, Cambodian and others.

Χηếτ τρονγ ηơν σốνγ đụχ – Better to die in honor than live in disgrace. (Vietnamese stone dedicated to those who gave their lives in the final days of the Republic of Vietnam.)

En mourant, afin qu’au moins l’honneur est sauf – Dying, so that honor at least may be saved. (Stone that serves as a memorial to the French who fell at the siege of Dien Bien Phu in 1954.)

Men Moulay Idriss djina Ja rebi taffou alina – We come from the Sultan. May God have mercy on our souls. (This quote comes from a marching chant of the Moroccan Tirailleurs. It honors Arab North African soldiers who fought with the French Union forces in Indochina.)

During his first visit, Ralph Pike focused on a few key words etched on the tablets. “Valor and honor and sacrifice – those three words,” says Pike, who served in the Army Reserve during the Vietnam era and is a member of Post 54. “It’s really what it’s about. It’s about defending our country, doing something for someone other than yourself.”

Soldierstone is “profound,” he adds. “I have been to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., where friends are memorialized. This is a little different.”

A DREAM REALIZED

The project took on a sense of urgency in April 1994, when Beckley was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

After receiving federal approval for Soldierstone to occupy national park land, he spent months planning the installation. When that time came, a team composed of volunteers, the Army’s 10th Special Forces Group, U.S. Forest Service personnel and a Colorado memorial firm completed the installation in one week. Soldiers took on the most difficult task: hauling the heavy stones up the mountain.

The memorial was dedicated July 14, 1995, in a small ceremony. Beckley’s poor health prevented him from attending, though the event’s details were relayed to him.

“When the Army chaplain began his blessing, it began to sprinkle, then the sun came out,” says Roy, whose brother died in November 1995 without seeing the memorial in person. “He thought it meant that God was blessing it. My brother had tears in his eyes, which was very unusual.”