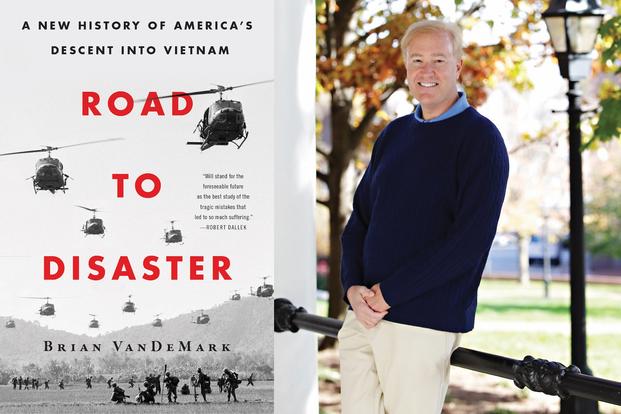

Brian VanDeMark's "Road to Disaster: A New History of America's Descent into Vietnam" is a startling read, a book that puts America's leaders on the couch and analyzes the psychology behind the decisions that led us into an unwinnable war in Southeast Asia.

VanDeMark comes to the subject with authority. He has taught the history of the Vietnam War to Naval Academy students for 25 years. He co-authored Robert McNamara's "In Retrospect" and was the research assistant for Clark Clifford's memoir "Counsel." This is a guy who's thought about the subject as much as anyone and "Road to Disaster" brings a lot of new perspective to the era.

In an excerpt that might just be on point here in 2018, VanDeMark discusses McNamara's unwavering loyalty to LBJ, even when the Secretary of Defense realized the truth about the war was something different than what the president wanted to hear. McNamara believed he had a greater obligation to the president than he did to the nation or the truth, a decision that ended in tragedy for a generation of young Americans.

Excerpt from Chapter 6: The Jeopardy of Conflicting Loyalties (May 1967–February 1968)

We live our lives in a set of intersecting circles of attachment. The complexity of loyalty is characteristically human, and in making difficult choices, people can act counter to some loyal- ties in order to further others. How does one make the right choice under such circumstances, especially when the stakes are immense and the trade-offs of vast consequence?

In Robert McNamara's case, by 1967 personal allegiance to Lyndon Johnson and institutional loyalty to the presidency had begun to conflict with his loyalty to the truth about the war as he saw it and the national interest of the United States as he understood it. McNamara had always been a team player who believed overt conflict between himself and the president undercut the morale of American soldiers and the American people.

"He thought . . . it was sinful not to present a united front," recalled a former assistant. "I don't believe the government . . . can operate effectively if those in charge of the departments of the government express disagreement with decisions of the established head of the government,"

McNamara said in an interview that he authorized for direct quotation. "I never discuss any recommendations I might have made to the President before the policy decision was made. To do so might strengthen my position but would weaken the President's . . . Our responsibility as Cabinet Officers is to the nation through the President [emphasis added]."

He had to support the president or keep quiet. To do otherwise was sabotage if not treason. "My constituency was one man—the elected representative of the people—and I was to do what he believed the Defense Department should do to carry out his objectives for the nation . . . The contract was that I would be totally loyal, but as part of that, I would tell him what I believed and, finally, I would ultimately do what he decided and support what he decided, or I would leave."

So McNamara remained publicly silent about his deepening pessimism, convinced that openly challenging the president would be disloyal and would elicit a more defensive and hostile reaction than would privately expressing his dissent—the logic of one who plays the classic insider's game. McNamara's excuse was less that he was following orders as he was attending to order. Yet in waiting for Johnson to set the alarm, McNamara continued to help wind the clock.

By the spring of 1967, McNamara saw Johnson persisting in a failing policy costing more and more American and Vietnamese lives with no successful resolution in sight. Johnson, in turn, sensed McNamara's deepening disenchantment and felt stung by it—after all, McNamara had pressured him to hold the line in Vietnam in 1964–1965.

"McNamara's gone dovish on me," Johnson complained bitterly to a visiting Senator, on another occasion muttering, "Bob's got a crew over there at the Defense Department, and they're under- cutting us on Vietnam."

But the truth was far more complex than the stereotype of a petty, intemperate, and callous chauvinist in the Oval Office. LBJ sometimes indulged spasms of anger toward those around him who voiced unwelcome news, but those he trusted could continue to speak their minds knowing he was ingesting their opinion.

In this way, McNamara's insights slowly affected and changed Johnson's thinking on the war. However much he fought the painful truth, Johnson gradually realized with bitterness and fatalism that he had fundamentally miscalculated and had steered himself and the country into a dead end in Vietnam.

But that realization came slowly in the latter months of 1967, and Johnson began acting on it only after he engineered McNamara's departure.

From "ROAD TO DISASTER: A New History of America’s Descent into Vietnam." Copyright ©2018 by Brian VanDeMark. Reprinted with permission of Custom House, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.