The Greatest Generation fought an epic struggle against an enemy that was identifiable in combat by the uniforms they wore and the hardware they employed. Battlefield gains were delineated in geographic terms. And, ultimately, there was a clear definition of victory.

In spite of the superlative label, those who fought during World War II didn't create the circumstances that sent them into harm's way; they simply did their duty as the nation required at the time.

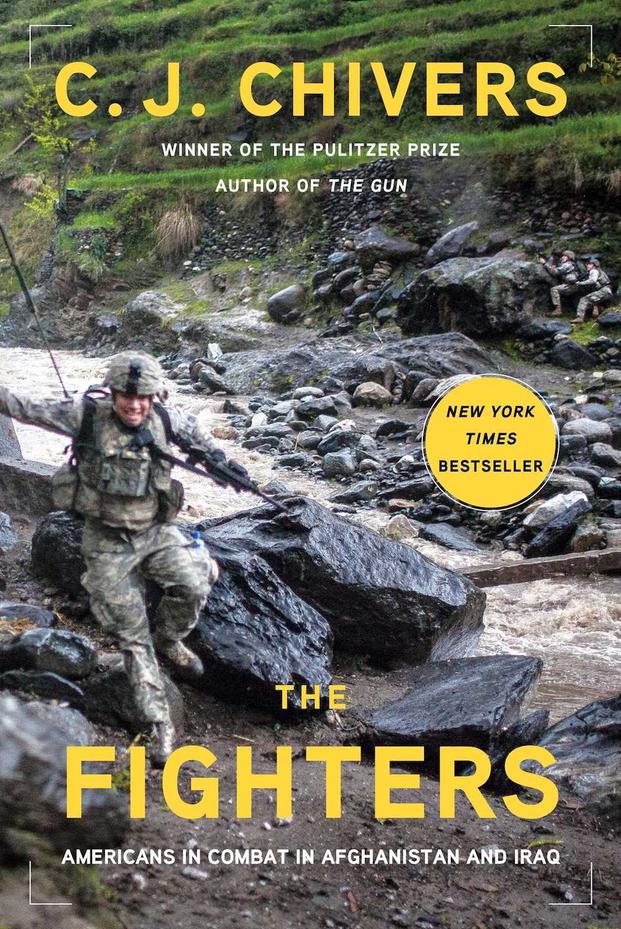

C.J. Chivers' "The Fighters: Americans in Combat in Afghanistan and Iraq" tells of a different era of conflict, one characterized by threats that rapidly change in form and lethality, an unsettled political landscape, and the absence of an end state.

Each chapter begins with a brief geopolitical synopsis that summarizes a point in time with a macro lens, but the book Is distinct in how the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter and former Marine Corps infantry officer captures the post 9-11 warfighting lives of six men: a strike fighter pilot, a combat medic, a scout helicopter pilot, a grunt, a platoon leader, and a Green Beret.

Those six service members come to the wars in one of two ways: a raw recruit full of idealistic notions of good and evil or a mid-career military professional ready to put his years of training to use at long last. Having accompanied them for years in the field as both a Marine and a reporter, Chivers relates the details of their lives with enough respect to leave their missteps and flaws in the narrative.

In the process, he presents the troops as they really are – not an abstract, some monolithic blob wrapped in cammie to be rolled out when it suits a political interest, but as individuals working hard to make their service and sacrifice have a semblance of meaning once it's over.

That meaning doesn't readily present itself even though the chain of command has insisted that there is a strategy to win at any given time. The two wars are distinct – Iraq is unrelentingly punishing in the worst years; Afghanistan is more episodic but no less savage – but they share themes inherent to asymmetric conflicts.

The enemy rarely appears in human form but instead announces its presence as a sniper's bullet or a roadside bomb. When the chaos subsides, the Americans are often left to figure out what happened by connecting dots as they come up with a satisfying narrative.

Following an extended firefight in Helmand Province, a lance corporal stands over the dead body of a Taliban fighter he just shot and announces that the corpse was the guy who'd killed one of their fellow Marines the day before (in spite of the fact there is no way to prove that). That synthesized payback scenario brings him joy.

The wars grind on. The nation has drawn from a very limited pool of warfighters, and each return to the fight exacts a greater toll on them, both physical and mental.

The book opens with the strike fighter pilot, a first-tour lieutenant aboard a homeward-bound aircraft carrier that gets turned around on 9-11 to execute the opening sorties into Afghanistan, and by the closing chapter he is his squadron's commanding officer flying over the same lands he did a decade before, except this time in a newer model of jet.

In his journal he writes, "As a [junior officer] I prayed to be able to see action and be in combat. Now I pray I don't have to see combat and can avoid having to drop [bombs]."

The combat medic is shot in the jaw by a sniper after months of attending to wounded Marines on the battlefields of Iraq. He returns home severely disfigured and goes through multiple surgeries. He battles depression. He goes through a divorce. He attempts suicide by driving his truck off of the road a high speed. "I tried to kill myself," he tells the first police officer on the scene. "And it didn't work." He's found guilty of reckless driving and put on probation.

In a surreal scene reminiscent of something out of "Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk," the medic and his mom get a short-fuse opportunity to meet with George W. Bush at the former commander-in-chief's office near a NASCAR event they're attending as guests of driver Kurt Busch.

As Bush talks to the wounded vet his tone vacillates between unconditional understanding and tough love. The medic's mom unloads her emotions in an extended soliloquy directed toward the president that leaves the others in the room stunned. "I am sorry," Bush says after a brief and uncomfortable silence. "I am responsible, I know. I sent him there."

Chivers calls Part II of "The Fighters" "Bad Hand," but that could just as well have been the book's title. It is also an apt metaphor for what was dealt to the more than 2.7 million Americans who have served in Afghanistan or Iraq since late 2001. Chivers deftly shows how these most recent wars thrust our combatants into trying situations without all of the tools they needed to win – whatever winning has come to mean in the last decade and a half.

But in telling the story through the perspective of those who actually fought it, Chivers also vividly illustrates what makes them worthy of a nation's respect and how they performed their duty as valiantly as any generation before them.

Ward Carroll is the Director of Outreach at the U.S. Naval Institute. He was the editor of Military.com from 2005-2014.