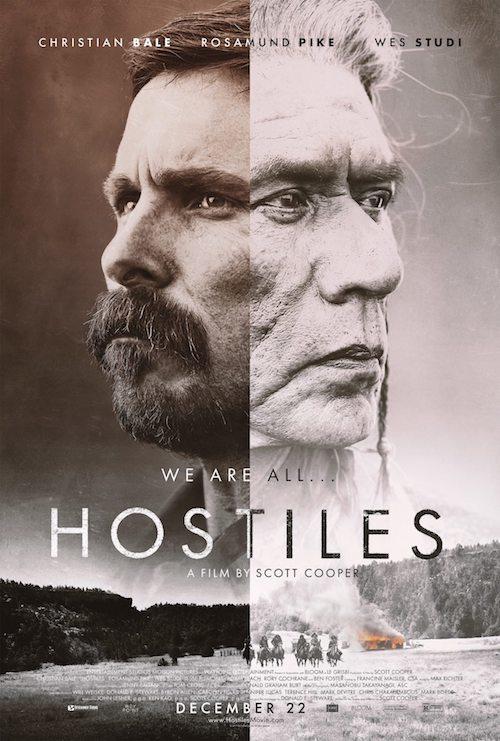

Native American actor Wes Studi has enjoyed a long career in movies, appearing in such classic movies as "Dances With Wolves" and "The Last of the Mohicans," as well as roles on the TV series "Hell on Wheels" and "Penny Dreadful." His finest part may be his latest role as Chief Yellow Hawk, co-starring with Christian Bale in Scott Cooper's fantastic new western "Hostiles."

In 1892, Army Captain Joseph Blocker (Bale) is ordered to escort a dying Cheyenne war chief (Studi) from prison back to tribal lands. Blocker and Yellow Chief faced off as enemies during the Indian Wars and he’s never gotten over the hate that fueled him in combat. They meet a young widow Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike) whose family was killed by Native Americans. As they travel from Fort Berringer in New Mexico to the Cheyenne homeland in Montana, they face attack from hostile Comanches and must band together to survive the journey.

It's a great picture, one that deserves to be mentioned alongside "Unforgiven," another classic that deconstructs myths of the Old West. It's not getting the awards season recognition it deserves so far, but it does open in theaters around the country this week after a limited run in New York and LA for Oscar qualification. It's definitely one worth seeing on a big screen.

Studi got on the phone to talk about movie but we ended up talking about his own service in Vietnam and why Native Americans commit themselves to military service just as much as we mentioned "Hostiles." It's a great movie about coming to terms with your enemies after the war is over.

Can you tell us about your military service?

I ETS’d out of South Vietnam in 1969. I was with Alpha Company, 3rd of the 39th Infantry, 9th Division, down in the Delta. That was my last service.

Is it true that you volunteered to go to Vietnam?

I was National Guard. I went to a boarding school in northern Oklahoma called Chilocco and the National Guard unit there was the 45th Infantry Division.

I joined up in my senior year. I got permission from parents to join when I was 17 or thereabouts and joined the National Guard mainly because we got to march around our school grounds and had a paycheck as well. For a while there, after joining, I went to Basic Training at Fort Polk, Louisiana, down with the pine needles and pigmy rattlers. Six months was the amount of time we had to spend there on active duty.

I got out and then I went to a few meetings and summer camps. At the time, we had a six-year obligation. I stopped going after a couple of summer camps, so I was activated into the regular Army. I still had my ER number, but I was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, upon activation and I joined a company there that was mainly a holding company for returnees from Vietnam.

When I was a part of that company, I heard so many stories of how bad it was over there but also how much fun it was over there. I heard all kinds of stories from guys who came back not just telling war stories, but telling stories of good times. The experience of it intrigued me. I have always been a person who wonders how I would do in a situation like the ones these guys would tell stories about. It just began to stay with me, that feeling of, Wow, I wonder what I would do, I wonder if I could measure up?”

So I volunteered. I had just about a year left of my six-year obligation. In a very short time, I landed at Thomson-Hood and went to Bearcat. I was assigned to the 9th Division and off I went. The first location that I remember was a place called the French Fort on one of the rivers very near the opening out into the Gulf.

I landed just as the Mini-Tet was starting up around the first of May of that year. I actually didn’t partake of all of the fighting that was going on there in Saigon. I think they decided to leave most of us who were new in country there at the French Fort, even though the company was very active in the defense of Saigon at the time.

We went on to move around all over the place, down in the Delta area, from base camp to fire camp to firebase camps. We mainly we traveled around by helicopter and by the boats on the rivers and patrolled moving around like that. We even rode helicopter boats and hovercraft. It was quite the time.

Eventually, I was off the line for about 30 days at the end and then was home sweet home, back to the world. Of the whole time I was there, I was the most nervous on that last day before we jumped on the plane. You never know when they were going to hit the airbase there.

One of the most interesting thing about “Hostiles” is how it examines the way warriors process the experience after the fighting is over. Your character and Christian Bale’s character are enemies who have to find common ground.

Right, and the common ground is a common enemy. That’s correct. I think that was the beginning of not necessarily a friendship, but at least a peaceful coexistence between former enemies who perhaps become actual allies in battle. That’s pretty much the history of humankind, how we come together when we need to, when we have to, in order to continue to survive.

One of the most interesting things about the PBS Vietnam War documentary in 2017 has been the insights from troops who went back to Vietnam and had contact with the men they fought against during the war. There seems to be a sense of respect for their former enemies.

Well, I felt that early on while in country, actually. I was reminded of who I was by many of the Vietnamese, like some of the – you know what a Chieu Hoi is? They were usually scouts who have surrendered, people who used to be VC or even NVA. They were guys who had surrendered and then volunteered to scout for us. One of the common things they said to me was, “Hey, you same/same Vietnami.” And you know I share their skin color and suppose I could of maybe even passed for a Vietnamese in certain circumstances.

I had the opportunity to visit an Vietnam Veterans of America convention this past summer in New Orleans and we did see a lot of that Ken Burns documentary. He sent us a lot of clips from different episodes of the whole thing, so I got a sneak peek at the beginning of it and then watched it later on, on PBS.

Of all the things that I've seen about Vietnam, which isn't a lot, I found it to be relevant to my way of thinking about things because I always felt that probably the worst part of the whole experience was coming home. As much as we wanted to come home, it didn’t really pay off.

The idea of almost immediately changing the way you live your life is not as simple as one would think. While we’re there, everybody wants to go home. When we got back, it wasn’t just the fact that there was so much protest going on about what we had been involved in and all that, but it was also the changing of our circumstances. There was no longer that imminent threat that we all just got used to. In Vietnam, the imminent threat of attack at any given time was always there. When we come home, we still kind of expect that to be there somewhere, but to act like that that’s the case made us all look kind of crazy, the crazy Vietnam vets.

The other thing that was disappointing was how the veterans of other wars looked on us, like we were crazy Vietnam vets. And then there was the mental recalibration you have to go through to adjust to peace. There's that old saying, I've heard it many times from veterans, “war may be hell, but peace is a killer too.” I found that to be very true and I myself was fairly useless for at least a year or two in terms of getting back into life as usual in the USA. Reentry was the most difficult part of the whole experience of going to Vietnam.

Another really striking thing about the film is how racism was used as a motivating factor by the US military as they dealt with the Native Americans during this era. Since that time, Native Americans have served in the military at a far higher rate than any other ethnic group. What is it about Native American culture that inspires men and women to serve?

Well, mainly because this is our land even though it’s being controlled by someone else now. At that time, we perceived that communism was an actual threat to us and to our life. The military is, for many Native Americans, a place to start out in life. Young men can connect with the military and do the protection thing and do what soldiers do, what warriors do. Many times it’s driven by a need, like poverty or needing something to do with your life at that certain point in time when you don’t have a profession or something like that.

Plus, at the time, they offered the GI Bill. It was a way to start out in life. Amongst themselves, Native Americans are treated with a lot more honor for having served the people. Our culture values the fact that our young men are willing and ready and able to put their lives on the line to protect others.