1932 was one of the worst years of the Great Depression in America. The unemployment rate ballooned to nearly 24%. Desperate people, pushed by economic and environmental disaster, took to the roads looking for work, food and shelter. For most Americans, there was no relief. For World War I veterans who were owed money from the federal government, they had one more option.

In 1924, WWI veterans won a one-time payment from Congress -- up to $625 -- for their service in the war. It might sound like a pittance, but when adjusted for inflation, that $625 would be worth around $16,000 today. The catch? It would only be paid out in 1945.

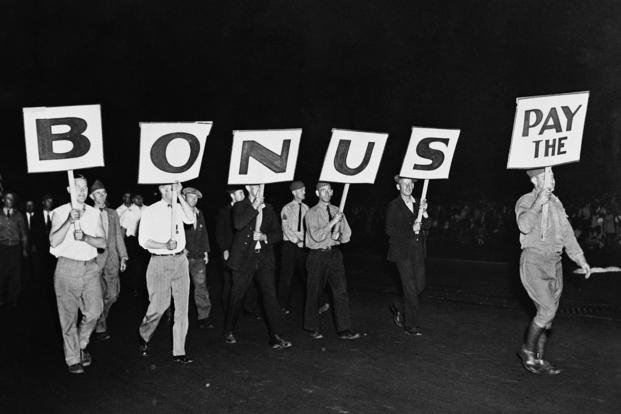

In May 1932, a group of veterans calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Forces decided that wasn't soon enough and made its way to Washington, D.C., to demand immediate payment. Dubbed the "Bonus Army" by the press, their ranks quickly swelled to nearly 20,000 (although some estimates suggest up to 40,000) as more veterans and their families -- unemployed, hungry and angry at their treatment -- set up camps along the Anacostia River and squatted in vacant federal buildings.

By most accounts, the camps -- three in total -- were generally peaceful and run well, despite being encampments made from cardboard and crates. The D.C. police superintendent was sympathetic toward the Bonus Army, providing blankets, securing transportation out of D.C. and even lobbying Congress for $75,000 to feed the group. Veterans gained permission to occupy at least some of the unused federal buildings in which they squatted. The racially integrated shantytowns were organized, requiring documentation of veteran status to squat in the area and included amenities such as a religious tent, a lending library and even a makeshift post office.

The veterans waited for a vote on a bill that would expedite their bonuses. In June 1932, the bill -- worth $32 billion today -- passed the House. In the Senate, John "Elmer" Thomas excoriated the chamber for its indifference, saying, "My fellow senators, are you proud of the record that has been made? ... Billions for big business, but not a sou [French coin] for soldiers!" After the Senate defeat, the majority of protesters left Washington but thousands still remained, likely because they had nowhere else to go.

Read Next: Hegseth Wants to Rename 8 Naval Ships. Here Are the Stories Behind Their Namesakes

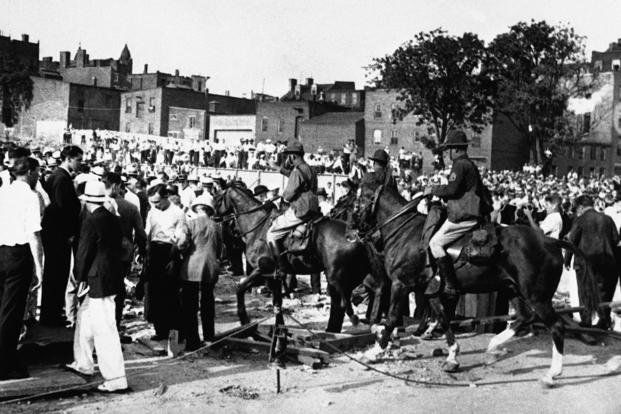

On July 28, things came to a head. D.C. officials, under pressure from President Herbert Hoover, ordered the city police to begin evicting remaining members of the Bonus Army. Two veterans were shot by police and died during an eviction -- with both sides saying the other started the violence. Local leaders requested federal help, recognizing an eviction of several thousand desperate people would take more manpower than they had.

Enter three of the most venerated 20th-century Army legends.

Douglas MacArthur, the Army chief of staff at the time, "personally led a contingent of six hundred infantry, mounted cavalry, and tanks into the city," with the goal to evict thousands of veterans and their families from their encampments. Dwight D. Eisenhower, MacArthur's aide, was adamantly opposed, later recalling, "I told that dumb son-of-a-b---h not to go down there. I told him it was no place for the chief of staff."

Also on the ground was Maj. George S. Patton, directing the troops under his command to fix bayonets: "If they are running, a few good wounds in the buttocks will encourage them. If they resist, they must be killed."

At first, there were rumors among the protesters that the Army would not march against their fellow veterans. Others thought that the Army was parading in their honor, even applauding the display of might. Excitement turned to horror when they realized the Army was there to remove them. Veterans challenged the troops but were gassed. Dubbing the operation "The Battle of Washington," TIME Magazine reported, "The unarmed [Bonus Army] did not give the troopers a real fight. They were too stunned and surprised that men wearing their old uniform should be turned against them."

Hoover twice sent word for MacArthur to end the military operation and not cross the Anacostia River, but the future supreme commander of the Allied Forces refused to obey White House orders both times. The Army ripped through the camps, razing them and eventually setting fire to structures in the evening.

When the smoke cleared, a baby had died, an 8-year-old boy had been blinded by gas, a 7-year-old boy had been bayoneted through the leg and two police officers and more than 1,000 protesters had been injured. Hearing news of the melee, Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat running against Hoover, reportedly commented, "Well, this elects me."

Patton's honor was tainted after the raid as well. During the event, he was approached by Joseph Angelo, a man who received the Distinguished Service Cross for saving Patton's life. Patton reportedly dismissed him from his sight, saying, "I do not know this man. Take him away and under no circumstances permit him to return." Newspapers around the country picked up the story and ran with it.

Officials, including Hoover, initially blamed the military intervention on provocation from Communist elements in the Bonus Army. Hoover ordered an investigation. Upon its release, he issued a statement, saying, "The extraordinary proportion of criminal, Communist and nonveteran elements amongst the marchers ... should not be taken to reflect upon the many thousands of honest, law-abiding men who came to Washington with full right of presentation of their views to the Congress. This better element and their leaders acted at all times to restrain crime and violence."

It was too little, too late. The Bonus Army attack was another nail in Hoover's political coffin. The public recoiled from the story and from the commander in chief as accounts circulated through the country. "If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America," the Washington Daily News opined.

Less than four months after the disastrous assault, Roosevelt won the presidency in a landslide victory. In 1936, WWI veterans received their bonuses.

It's impossible to know the true impact the bonuses had on thousands of military families across the country. At least one family turned theirs into a legacy: Actress Jennifer Garner's grandfather used his payment to purchase a farm in Oklahoma -- one that's still in the family today.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.