Nearly a year had passed since the bombs exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The world knew the power of atomic weapons; the Cold War was dawning.

Yet, in Los Alamos, scientists were still "pushing uranium around with screwdrivers."

On May 21, 1946, Dr. Louis Slotin suffered a fatal dose of radiation while he demonstrated the technique of critical assembly and associated studies and measurements to another scientist.

Critical assembly involves bringing two or more pieces of fissile material together to form a critical mass, the mass at which atomic chain reaction occurs.

The technique, called "tickling the dragon's tail," allowed Slotin to calculate critical mass, which would be necessary to detonate in an atomic weapon.

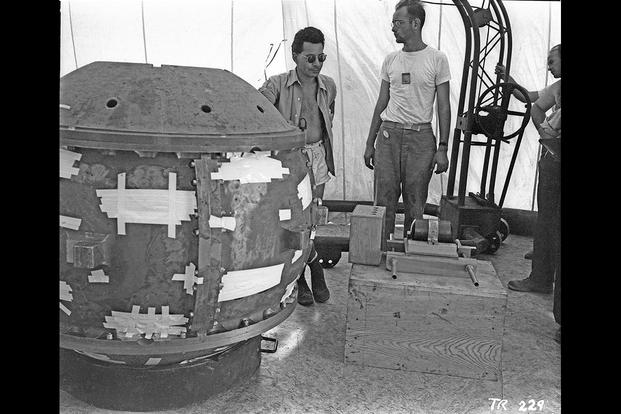

The method involved delicately screwing two hollow spheres of beryllium around a mass of fissionable material. Two one-inch spacers between the upper hemisphere and the lower shell provided the only "safety" measure preventing inadvertent critical assembly.

During a normal procedure, the spacers were removed to allow one edge of the upper hemisphere to rest on the lower shell while a screwdriver supported the other edge of the upper hemisphere. The operator would then lower the screwdriver bringing the remaining edges together.

Meanwhile, a Geiger counter would record the radioactivity as the operator brought the masses together.

During Slotin's demonstration, something went terribly wrong. As he slowly allowed the latter edge to approach the lower shell, one hand held the screwdriver while the other hand was holding the upper shell with this thumb placed in an opening.

At that time, the screwdriver apparently slipped and the upper shell fell into position around the fissionable material. A "blue glow" appeared; a heat wave moved through the room. "Slotin lunged forward and grabbed the two hemispheres with his bare hands, ripped them apart and took the full brunt of a nuclear detonation right in his stomach," says Dr. Michio Kaku, a famous atomic scientist.

Slotin immediately understood what had happened. As a result of the accident, he died nine days later, his body decomposing from the massive dose of radiation. During the nine days before he died, he insisted that his physical state be continuously documented so that the effects of radiation could be used for scientific purposes.

His assistant had also suffered enough radiation to cause serious injuries and some permanent partial disability. The six others in the room at the time of the accident suffered no permanent injury.

The tragic event of May 1946 foreshadowed many accidents in the Cold War to follow and suggested an early cavalier attitude shared by scientists and strategists toward the atom and its power. The lasting lesson of Slotin's death remains that human beings perform the procedures that make up science, military and industry and with human participation comes a fallibility and unpredictable element that, with nuclear power, can turn tragic very quickly.

As the collective understanding of atomic nuances grew and continued to evolve, the cavalier attitude dimmed as whole nations began to look for ways to cap the nuclear genie's bottle and serve as better stewards of these atomic secrets.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.