When John F. Kennedy was asked about what he did to become a hero in the Pacific War in 1943, he responded by saying, "It was involuntary. They sank my boat."

The truth is that Kennedy was a hero, whether or not the Japanese sank his boat. His capacity as a strong swimmer from his days on the Harvard swim team, his leadership as a U.S. Navy officer and his faith in his crew saw him rescue the survivors of a failed attack on an enemy flotilla and lead them to ultimate safety.

Kennedy's boat was PT-109, a patrol torpedo boat operating in the Solomon Islands. PT boats were designed to be small, fast and cheap to build while packing a punch with Mark-8 torpedoes and .50-caliber anti-aircraft guns. The glaring problem with the Navy's PT fleet was that its torpedoes often didn't work as planned, as the crew of PT-109 found out one night in 1943.

The future president was almost rejected for naval service. Kennedy had a long history of illness and injury as a child, some of which followed him into adulthood. Many of his ailments made him potentially unfit for military service. The most apparent of these was his chronic back pain, for which he underwent at least four major surgeries throughout his life.

On top of his back issues, as an adult, he suffered from asthma, ulcers and Addison's disease, an adrenal condition that affects bodily hormones and blood pressure. Still, he was a Kennedy, and his father pulled some strings to get him into the Navy in 1940.

By April 1943, Lt. Kennedy was stationed in the Solomon Islands, taking command of PT-109 and the 12 other crewmen aboard. Their primary mission was to patrol the straits between the islands and disrupt the nightly supply runs made by Japanese destroyers in the region, an operation the Allies dubbed "the Tokyo Express."

On Aug. 1, 1943, 15 patrol torpedo boats were deployed to intercept four Tokyo Express destroyers trying to reinforce the Japanese position on Kolombangara Island. Divided into four attack squadrons, the PT boats had 60 torpedoes to shoot at the destroyers -- but things went wrong almost immediately.

The Americans had missed the Japanese flotilla by an hour, and the enemy position was successfully resupplied. The PT boats were going to hit the Tokyo Express on its return voyage in the dark, early morning hours. When the PT boats that did encounter the Japanese found their targets, they fired their torpedoes. Not a single one exploded, which was the primary issue with Mark-8 torpedoes at that point in the war.

Only four of the boats had radar to use in the coming night attack, and when they fired off their torpedoes, they returned to base. This left the remaining boats with no way of finding their targets, and an order for radio silence compounded the confusion. Those that didn't have radar to locate the enemy ships would end up drifting around in the dark.

As the night drifted on, Kennedy idled the engines of his boat to reduce its wake and visibility from potential spotter planes. At around 2 a.m., they noticed the Japanese destroyer Amagiri coming right at them at full speed, lights out. The warship hit PT-109 on its starboard side, cutting the boat in two.

The fuel aboard the boat launched a fireball into the air, lighting up the night sky. Two crewmen were killed instantly. Two others were thrown into the ocean. The other boats in the squadron tried to fire at the Amagiri, but two of their torpedoes missed, and two others wouldn't fire at all. They returned to base without checking for survivors.

Kennedy dove into the flaming water surrounding the wreck of PT-109 to pull three crewmen aboard what was left of the boat. The Amagiri departed the scene, needing to return to port before American spotter aircraft began searching for ships at dawn. Kennedy and his 10 remaining crew held on to the floating bow of PT-109 for the next 12 hours.

They drifted toward Plum Pudding Island, a small uninhabited island that was 3.5 miles from their position as the sun rose that morning. Clinging to a log used as a gun mount, most of the crew collectively kicked its way to the island. One of the survivors, Machinist's Mate 1st Class Patrick McMahon, was critically wounded. With burns over 70% of his body, he was unable to swim.

McMahon was put in a life jacket, and Kennedy, with the life-jacket strap clenched between his teeth, swam his crewman to the safety of the island, a four-hour effort. It was all for naught, however. Though the crew was safe from drowning, Plum Pudding Island offered no food or water.

Kennedy's swimming ability became critical for the next few days. Despite his chronic back pain, he swam to try to hail passing American PT boats. He then led the hungry and thirsty crew on a nearly four-mile swim to Olasana Island, which had edible coconuts. Kennedy made the trip with McMahon's life-vest strap in his mouth once more.

He then swam to Naru Island with another crewman, where he found an abandoned canoe with some food and a drum of water left by the Japanese. Kennedy paddled the canoe to his men on Olasana. For six days, they subsisted on a few coconuts, the captured food and rainwater caught on leaves.

Two native Melanesians who had been trained as coastwatchers by the Allies were dispatched to look for survivors of a Japanese shipwreck. These islanders could move freely during the day as they were dismissed by the Japanese as native fishermen. On Aug. 5, they discovered the survivors of PT-109.

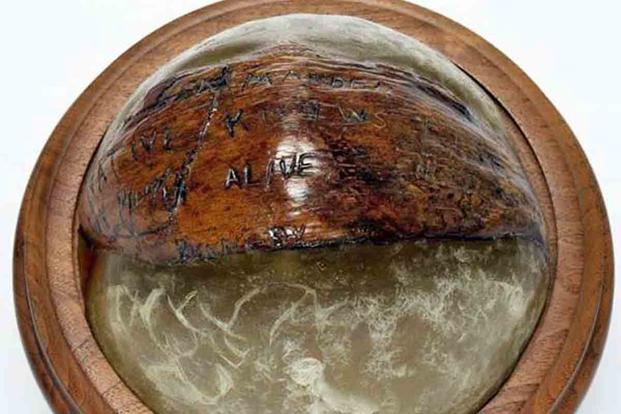

Kennedy and his executive officer, Ensign Leonard Jay Thom, both made messages for their command. Thom scrawled his on a slip of paper with a pencil. Kennedy etched one out on the skin of a coconut. The coastwatchers got the messages to the right people, and the crew was rescued on Aug. 8.

Kennedy was hailed as a hero who had returned from the dead. Though PT-109's officers had all been instrumental in their survival, the media focused on Kennedy, who was the son of the famous businessman and former ambassador to the United Kingdom. Though he returned to duty after being presented with the Navy and Marine Corps Medal and Purple Heart, the incident exacerbated his ongoing health problems.

As for the Tokyo Express, Adm. William "Bull" Halsey met the Japanese destroyers with six American destroyers. The U.S. Navy surprised the enemy resupply convoy while the crew of PT-109 was marooned on Naru Island and sank three of them without taking a single loss.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.