In 1935, fascism was on the rise in Europe and Asia, but the world had not yet had to fight its territorial expansion on a global scale. Adolf Hitler had been elected as chancellor of Germany just two years prior, and Hideki Tojo was still six years away from bringing the United States into World War II.

But Benito Mussolini, who had been in power in Italy since 1922, was bent on finally conquering Ethiopia. It would erase Italy's failure at the 1896 Battle of Adwa that secured Ethiopia's independence and kept it from becoming a European colony while establishing Italy as a major world power.

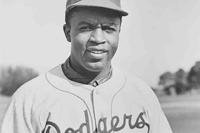

Leading Ethiopia's young air force was Black pilot John Robinson, a young activist and aviation enthusiast who blazed a trail of Black men flying into combat against fascist dictators.

Robinson, a former shoe-shiner and warehouse worker, left his home in Mississippi after the 10th grade to earn a degree in auto repair from Alabama's famed Tuskegee Institute. He traveled around the country looking for work, but had a hard time finding someone who would hire a Black mechanic.

His persistence paid off, and he eventually found himself working in a garage doing what he loved. But he had a new dream: flying. While working in a Detroit garage, he met Cornelius Coffey, a fellow mechanic. The two were inspired by the achievements of Chicago's Bessie Coleman, the first Black woman to receive an international pilot's license. Coleman famously encouraged Blacks and women to learn to fly.

Coffey and Robinson applied to the Curtiss-Wright School of Aviation in Chicago and were accepted -- until the school learned about their race.

The school repeatedly denied Robinson's applications to attend, so he took a job as a janitor and sat in on classes anyway. He was an attentive student, even if he wasn't technically enrolled. He learned so much, he built his own aircraft with Coffey, using an old motorcycle motor. It was a feat that finally inspired the school to accept them as students.

Soon, Robinson had a pilot's license of his own. He didn't stop there, however. He and Coffey founded a Black flight school, the John Robinson School of Aviation, in Robbins, Illinois, a predominantly Black suburb of Chicago. Though the school hired them to teach Black pilots, the two were not allowed to use White airstrips.

So they built one by hand.

Black aviators in Chicago, led by Robinson and Coffey, formed the Challenger Aero Club. Its first plane was purchased for the group by a fellow student, Janet Harmon Bragg, and they flew training classes from the airstrip until it was destroyed in a storm.

After moving to Harlem Airport on Chicago's south side, word began to spread that other Black pilots could train there. Many of the U.S. Army Air Forces' future Tuskegee Airmen learned to fly at Harlem.

Robinson soon contacted his alma mater, the Tuskegee Institute, to establish a flying school for Blacks there, when funds were available. The school was founded in 1939, and after the war, Robinson became known as the “Father of Tuskegee Airmen.”

That was his second nickname. His first came from flying for the Ethiopian Air Force

In 1935, Italy was bullying Ethiopia for territory in East Africa as European powers and the League of Nations looked the other way. Robinson volunteered to go to Ethiopia and fly in service to its emperor, Haile Selassie I. When the emperor learned about his new volunteer, he extended an invitation for Robinson to come and teach his pilots how to fly.

Robinson was appointed commander of the Ethiopian Air Force by August 1935. He didn't have much to work with -- about 19 unarmed biplanes and 50 pilots. But his men were able to fly reconnaissance and resupply missions to Ethiopian troops in the field. They were outmatched by the superior combat aircraft the Italians were flying. Still, Robinson’s skill and daring in the air earned him the nickname "the Brown Condor."

That October, Italy invaded in full force, and Ethiopia was crushed. The war lasted just seven months before Ethiopia was annexed by Italy. Robinson returned home to the United States, where he received a hero's welcome.

Coffey, in the meantime, had befriended an Army Air Corps officer named Noel F. Parrish. Parrish was suitably impressed by the school at Harlem Airport and, by the time the War Department appropriated funds to train Black airmen in 1941, Tuskegee University had been training pilots for two years. Parrish was soon named commander of Tuskegee Army Air Field, overseeing the training for the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for fitness and basic training tips, or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.