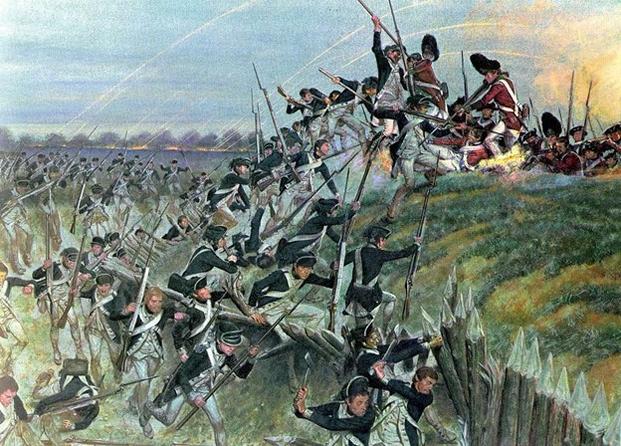

On Sept. 16, 1776, musket balls tore through the air at Harlem Heights, New York, as Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton led his Rangers against British light infantry. Ordered to flank the enemy, his men instead charged head-on into overwhelming volleys of gunfire. Outnumbered and outgunned, they pressed forward until Knowlton fell, mortally wounded. The first American unit created for intelligence and irregular warfare was shattered in its very first battle.

It was a failure on the field, but the beginning of a tradition that shaped U.S. special operations and espionage for centuries to come.

America’s First Special Operations Force

Weeks earlier, Gen. George Washington had realized his army needed more than raw courage to survive the Revolution. He needed intelligence, and quickly.

He turned to Knowlton, a veteran of Bunker Hill and the French and Indian War, to raise a new elite infantry unit of about 130 men from Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Many were farmers and schoolteachers; only a few were combat veterans. Their mission was unprecedented: scouting, spying, and irregular tactics behind enemy lines. They became known as Knowlton’s Rangers, the first American military intelligence unit.

But Knowlton and his men were learning on the fly. While they were brave soldiers, they had little training in the world of espionage. The British, by contrast, had a sophisticated network of spies directed by Maj. John André. He was supported by agents such as the notorious Maj. Robert Rogers, the man who founded the original Rogers’ Rangers during the French and Indian War.

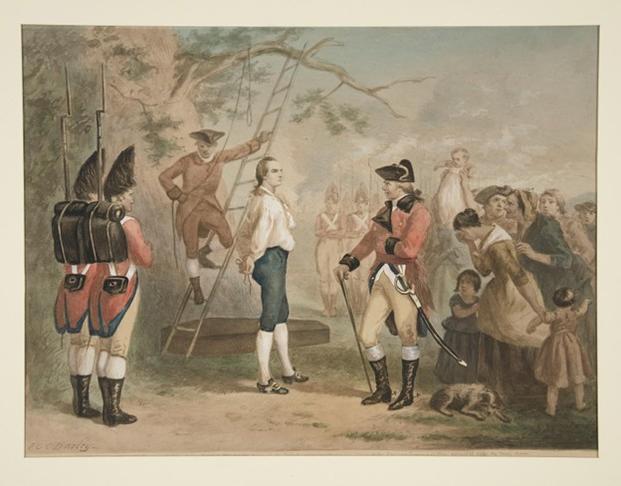

The imbalance became tragically clear in September 1776. Only a week after Knowlton’s death, Capt. Nathan Hale, one of his Rangers, slipped into British-held New York on a covert mission to track enemy movements. Rogers deceived him by posing as a fellow patriot, tricking Hale into revealing his objectives. Hale was captured and hanged, reportedly declaring, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” His death exposed just how unprepared the Americans were for intelligence work.

Knowlton and Hale were dead, the surviving Rangers scattered, and most were eventually captured after the fall of Fort Washington. On paper, the experiment had failed.

Washington Learns the Value of Intelligence

Even in defeat, Washington had a talent for spotting opportunities. The war could not be won without spies and intelligence. After the deaths of Knowlton and Hale, Washington authorized the creation of the Culper Spy Ring, a civilian and military network that operated in and around New York City. Unlike Knowlton’s Rangers, the Culper Ring specialized in secrecy, codes and long-term espionage. The actual names of the agents were kept secret even from Washington.

The ring’s efforts paid off. It exposed Benedict Arnold’s treason and led to the capture and execution of Maj. John André, Britain’s top intelligence officer in the colonies. Using its covert tactics, the Culper Ring also uncovered British plans to flood the colonies with counterfeit currency, foiled a plot to assassinate Washington, and disrupted an ambush targeting the newly arrived French forces in Rhode Island.

By 1781, Washington had created a successful strategy that combined infantry, guerrilla forces, and military intelligence. In the South, Francis Marion and other partisans harassed British supply lines, raided garrisons, and forced the enemy to retreat from key positions, gradually pushing the British out of the southern colonies. Many of these troops continued to gather intelligence while engaging the enemy directly.

Meanwhile, the Culper Ring provided Washington with critical intelligence on British troop movements toward Yorktown, Virginia. They also helped convince the British that a French force was preparing to attack New York, tying down any potential British reinforcements. These deceptions allowed the French fleet to blockade Chesapeake Bay while the American and French armies encircled Yorktown. The coordination of southern guerrillas, the Continental Army, and intelligence networks led directly to Lord Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, effectively ending the war.

A Lasting Legacy

Though short-lived, Knowlton’s Rangers established the idea that elite soldiers could fight behind enemy lines and collect intelligence to shape strategy.

While the lineage of modern U.S. Army Rangers reaches back to Rogers’ Rangers, Knowlton’s troops were the first Americans to practice the craft.

Other special operations forces, such as Green Berets and Delta Force see them as forerunners of their missions as well. The CIA and DIA also recognize them as the first American organization built for intelligence work. The year “1776” on the seal of the Army Intelligence Service is a direct reference to Knowlton’s Rangers.

They may have been cut down at Harlem Heights, but their legacy forced the United States to embrace espionage and irregular warfare, principles that not only helped secure victory at Yorktown but remain central to America’s most elite forces nearly 250 years later.