Bill Ivory is a Vietnam War veteran who served with 1st Marine Division in 1967 in Da Nang. He lives in Kensington, Md.

That life on this day remains the primary focus doesn't mean certain tasks remain unaddressed ad infinitum. For the family and friends of one Navy petty officer, opportunity to carve a noble inscription provided opportunity to revisit a brief life well lived.

Charles R. Trescott died heroically on May 3, 1966, in Quang Tin Province in South Vietnam, after leaving a covered position to aid a fellow Marine. We were classmates at Salesian Catholic in Detroit. We ran in different crowds but the relentless equilibrium wrought by alphabetical seating plopped us side-by-side, trading in day-to-day high school banter.

At graduation in June 1964, we crossed the stage of the nearby Rackham Memorial Building to receive diplomas. A traditional hinge point in American life completed, we shook hands and strode off to experience the mystery of whatever may come next. I knew he served in the Naval Reserve, which filled me with vague notions of him soon sailing the oceans blue.

I can't recall how word of his death came to me. I suspect a dear aunt and family herald provided the alert. Each morning Elaine scoured, as if holy writ, the obituary pages of the Detroit Free Press.

At his wake, held at one of the area's longest-serving funeral homes, Charley lie in repose between the Stars and Stripes and the Navy flag. His dress uniform hardly obscured the fact that at the time he remained still too young to vote. Turns out, he served as a medical corpsman attached to a Marine infantry platoon. My assumptions of life cruising the high seas now obliterated, an ominous sense welled in me akin to the gray emissions oozing from the nearby Ford Rouge steel plant.

The requiem took place the next day. I was elsewhere -- eight miles southwest, to be exact, at the Fort Wayne induction center. There, along with 40 others, I took an oath to preserve and protect the Constitution of the United States of America. An evening flight deposited us at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego. Autumn 1967 found me with the 1st Marine Division Da Nang. Charley remained ever in my thoughts.

Infantry was not my billet, but I too spent what seemed endless days slogging through these quilt-like grids of harvesting rice. Today, tour buses rumble the countryside filled with the curious hoping to experience The Experience -- of course, in safe, air-conditioned, engagement-free comfort. I laugh in a wincing kind of way and wish that Charley were here to share the chortle.

Fortune favored me. I made it back to the U.S. in one piece, able to live a life. After some extended, post-discharge travel I settled in the Washington, D.C. area. Contact with Detroit remained consistent but far less detailed. Charley, I eventually learned, was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Trescott family's participation in the U.S. military extends back to the Revolutionary War. His dad was held prisoner in a Nazi camp. It seemed fitting that Charley, as the last family male heir, would take final rest in the nation's most hallowed ground.

Section 51 stretches on an almost direct line from the Cemetery Memorial Bridge gate across gentle slopes toward the Iwo Jima Memorial. Rene Gagnon, one of the figures depicted in the iconic bronze statue, lies buried at its northern tip. On my first visit, wreaths still lay atop graves of the newly interred. At the time, a tree line of recent planting allowed clear view across the Potomac, revealing the Lincoln Memorial and the yet-to-be dedicated Kennedy Center. It was a very special moment, a grateful opportunity to provide small company for someone now lodged in the narrative of our lives more as comrade, less as schoolmate.

Many of the recently interred were Vietnam veterans. The only Americans avoiding discussion of Vietnam in 1969 seemed to be the many who served there. Lingering among those who might best understand just why this avoidance proved comforting, almost peaceful.

Once again, longitude and latitude meant delayed notice of neighborhood events. The announcement that Charley was awarded the Silver Star escaped my notice. The citation detailed his work to save two men cut down by ambush fire, how he refused to leave their side, worked furiously, courageously to stabilize wounds prior to evacuation.

Corpsmen are a constant presence in Marine Corps field life. I found their skill and poise most admirable. I occasionally wondered if they chose Vietnam or did the press of war dictate otherwise. I never asked, of course, least unspoken juju be disturbed. Here we were. That was the fact. Undue reflection could prove distracting, dangerous.

Years pass, priorities change. Work, family, the manner of simply being a citizen among citizens require different attentions. In time, a part-time job with a suburban Maryland funeral home occasioned me to be present at Arlington on a regular basis. Interments, I noticed, in Section 51 now occur far less frequently while monumental Washington stands hidden by a mature tree line.

Participation in many graveside services also provided me with an opportunity to observe an occasional stone inscribed with additional biographical inscription. Purple Hearts were frequent additions. Scans would sometimes reveal Medals of Honor, Bronze and Silver stars. Occasionally commendations from other nations pushed into view. Arlington's intrinsic beauty is enhanced by its purposeful uniformity, the standardized stone weathering but withstanding an endless march of days. Occasional inscription tweaks provide just enough variety to encourage continual close attention.

Charley was buried, the stone long set, prior to the medal award. Complete recognition of his extraordinary valor had been misplaced in the natural shuffle of the work place. It occurred to me that perhaps action could be taken to rectify this unintended slight. I began making inquiries.

Guidelines uniform to all military cemeteries dictate markers can be altered only upon written permission from next of kin. So, the first step was to contact a family member. I soon discovered how years spent afar weakens what were once strong regional connections -- that networks believed maintained simply fade into mere loose associations. With Charley's parents deceased and his siblings now also among Detroit expatriates, my initial attempts to make contact with his family proved futile. In an age of ubiquitous social media, search engines galore, the trail to the right Trescott continued cold.

Over the years, the class would hold the occasional reunion. The most recent assembly convened at a restaurant across the street the Rackham Building. Over coffee and dessert, I began relating various Charley adventures to fellow Knight, Rich Bartus. Intrigued and recently bestowed with some spare time, he volunteered to provide new eyes to the Michigan end of the hunt.

Rich soon experienced similar false starts and unproductive leads. Then, he caught an incredible break. A casual discussion with the attending funeral director at a friend's memorial service revealed a local auxiliary military chaplain was a relative of Claire Trescott. We found out she practiced medicine in Seattle. What's more, Claire was to soon return to Michigan for a family reunion.

So began a flurry of far more productive calls. Rick was invited to the reunion, where he explained our quest to the amazed, slightly stunned Trescott sisters. The needed paperwork was drafted on the spot. Thoughts of doing a dedication became the small talk of the event. It was Aug. 3, 2016 -- what would have been Charles Robert Trescott's 70th birthday.

After 50 years, this long-delayed acknowledgement began to come together with startling ease.

The National Cemetery Administration was attentive to our request and most helpful through the entire process. Placement of the new stone estimated to take 90 days was completed in half that time. This allowed us to start planning a dedication for the spring or summer period.

With my focus on marker-related tasks, I had neglected to monitor the Vietnam Memorial Wall website and for sometime overlooked a long-posted note. Mike Rowan met Charley while they and the rest of the 26th Marines assembled and trained at Camp Pendleton prior to the units' March 66 deployment to Vietnam. Mike could recall shipboard training, early environment acclimations, details of long ago firefights.

For some time, Mike had been in contact John Ernst, their platoon commander Gulf Company, 2nd Battalion 5th Marines. It was Ernst who prepared the recommendation for the award. Both men kept the platoon photograph on their home desks. Charley standing at attention in the front row was hard to miss much less forget. Mike in Chicago, John in Los Angeles were eager to participate in any event we could organize.

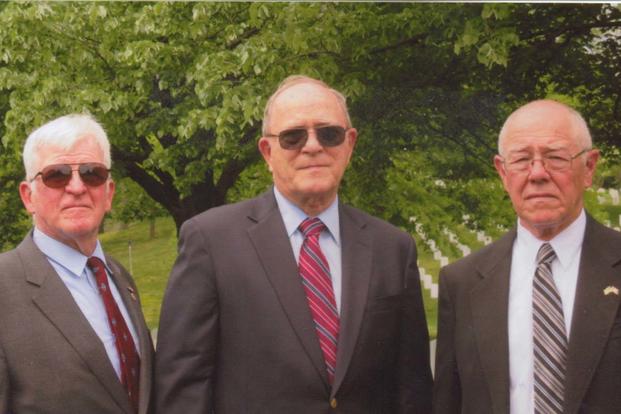

Rich began contacting the other classmates. A headcount revealed several others who served in Vietnam, two purple hearts among them. Pat Hayden, a recently retired electrician, was eager to include the dedication with a long-delayed pilgrimage to The Wall. Several local friends of Vietnam service helped with logistical support. Jim Mayer, who achieved a measure of fame as the Milkshake Man in the Doonesbury cartoon strip, became unofficial "jeep driver" collecting out of towners for transport to the Cemetery. This gathering seemed to be composing itself in crisp military style, every organizing move propelled by a long simmering energy.

April 21 arrived mail-order perfect, complete with a slight breeze, high blue skies, springtime Washington at its most glorious. After a brief welcome, David Naylor, provided a moment of prayer and reflection. Speaking for the family, Claire confirmed how her brother remains ever in their thoughts and how so much he is missed. Mike and John again confirmed Charley's courage and dedication, provided some insight on how events unfolded that long ago spring day. Father Sam Giese, Army chaplain and Iraq veteran, blessed the new stone. The plan was to place personal mementoes, then retreat to a luncheon at nearby Fort Meyer.

But there was more -- a last-minute unexpected contribution.

Thanks to a lead generated from a high school reunion website, an additional voice brought surprising detail and additional closure to the proceedings. Melissa Ridgely Covelesky's father was best friends with Steven Sherman -- one of the Marines whom Trescott tended that day in Quang Tin.

They grew up on adjacent farms in Howard County, Maryland. Melissa's brother is named in Steve's honor. The severity of his wounds necessitated evacuation to the States to undertake more extensive stabilization. In time, he was sent home to Maryland, where he died in July. Covelesky, now a lieutenant colonel in the Army Judge Advocate General's Corp, soon to be stationed in South Korea, related in some detail the appreciation felt by all.

This fond gathering assembled only to fully recognize a long-ago honor now gently verges into a moment of deeper reflection. Charley's incredible efforts ensured extension of one man's days. True. But unseen then and perhaps until this moment was the creation of a profound gift. An opportunity for citizens in a faraway place, unseen, unknown, to experience the priceless opportunity of mutual solace and extend face-to-face goodbyes. More is etched here now than mere valor. Instead it restates the continuing relevance and profound contributions radiating still from an all too short life.

Rest in peace, corpsman, rest in peace.

-- The opinions expressed in this op-ed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Military.com.

-- If you would like to submit your own commentary or op-ed, please send your article to opinions@military.com for consideration.