The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, passed during the post-Reconstructing era, is the cornerstone of the legal wall separating the U.S. military from domestic law enforcement. For much of Reconstruction, federal troops had enforced civil rights protections in the South, and many lawmakers pushed to end what they saw as a military occupation. The act prevented using federal troops from carrying out policing functions – such as searches, seizures, and arrests – unless Congress expressly authorized it by statute. The law does not apply to the Guard when under state control but does when they are federalized.

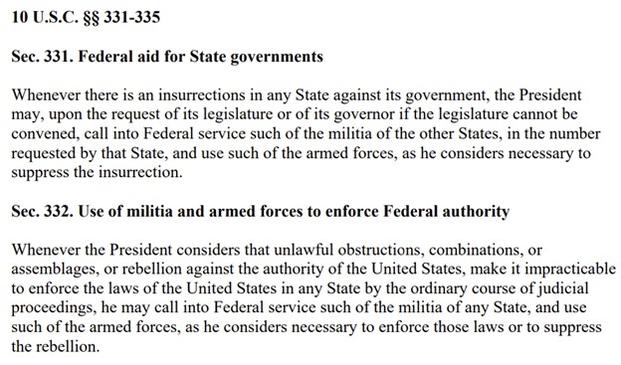

The most important exception is the Insurrection Act. Unlike Posse Comitatus, which limits military involvement in policing, the Insurrection Act empowers the president to use federal troops inside the U.S. in defined situations: at the request of a state facing insurrection, when normal judicial enforcement of federal law becomes “impracticable,” or when state governments fail to protect constitutional rights in the face of violence. The law requires a proclamation ordering insurgents to disperse before force is used. Once invoked, it authorizes direct policing by federal troops without violating Posse Comitatus. It has been used more than 20 times. These laws leave the president with latitude but also set up legal and political conflicts whenever active-duty soldiers are used on American soil.

Recent Deployments Under Scrutiny

Recent coverage describes how this framework is being tested. President Trump has ordered Guard units and other federal forces into cities like Washington, D.C. and Portland, sparking lawsuits from state officials who argue the deployments violate Posse Comitatus by crossing into law enforcement. Courts are now being asked to determine whether these troops are providing support – which is permissible – or engaging in policing, which would be unlawful.

The border has been another focal point. Reports detail how the administration sought to place parts of the “Roosevelt Reservation,” a strip of land along the U.S.-Mexico border, under DoD jurisdiction. That shift would allow active-duty troops to operate there with fewer legal constraints; a move critics describe as an attempt to sidestep Posse Comitatus restrictions. While the military has historically assisted with logistics and surveillance at the border, direct apprehension of migrants would move into prohibited law enforcement activity.

Washington, D.C. has also become a test case. In August, the Pentagon announced Guardsmen patrolling the capital would be armed, marking an escalation from earlier unarmed security patrols. The move drew concern because while the Guard can be mobilized domestically under state governors, its federal activation in the capital puts it squarely under presidential authority and arming them raises the question of whether their role remains support or slips into direct law enforcement.

The Question Of Unlawful Orders

Some have also examined the scenario of a president issuing an order that is arguably illegal under Posse Comitatus. Military leaders are obligated to follow only lawful orders, and longstanding precedent holds that “just following orders” is no defense if those orders break the law. Yet the political and institutional pressure to comply with presidential direction can be overwhelming. If the military were instructed to police U.S. citizens in defiance of statute, commanders would face a stark choice: obey and risk illegality or refuse and confront the commander-in-chief.

Broader Risks

The Posse Comitatus Act was written to keep federal troops from becoming a domestic police force. This is not the first time the line has been tested, and the current use of troops in cities and at the border is the latest push. States such as California are already fighting these deployments in court, reaching back to nineteenth-century precedent to argue federal authority has limits. Whether those limits hold, or whether the White House eventually invokes the Insurrection Act to override them will set the tone for civil-military relations going forward. This is not an abstract debate. It is a live question of whether U.S. soldiers will be treated as a reserve police force – or whether the statutory line that has held since 1878 will actually mean something when it’s tested.