Brenner M. Fissell is an associate professor of Law at Hofstra University and vice president of the National Institute of Military Justice. Philip D. Cave is a partner in Cave & Freeburg LLP and a director (and past president) of the National Institute of Military Justice. He is a retired Navy judge advocate with 41 years of military law experience in courts-martial and appeals.

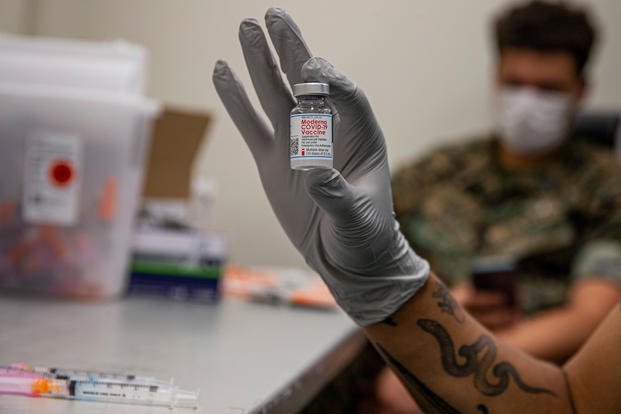

Some service members are objecting to mandatory COVID-19 vaccinations. At the moment, there is no order compelling them to take the vaccine, allowing them to decline immunization without punitive consequences. That will change should President Joe Biden grant a written waiver using his authority under 10 U.S. Code 1107 to compel military members to take even authorized but unapproved vaccines. Reports suggest Biden has set a Sept. 15 deadline for doing so, and a recent Office of Legal Counsel opinion supports that such an order would be lawful.

An emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration allows the use of one of three available COVID-19 vaccines, and there's no clear timeline for full FDA approval. Because of this emergency status, a service member currently must give consent to be vaccinated.

Service members are asking experienced military lawyers the "what if I ... " question. There are some answers based on prior experience with the anthrax vaccine mandate. In addition, people serving in the military are already required to be vaccinated against many infectious diseases.

In the 1990s, the Defense Department established a mandatory anthrax vaccine program, and there were refusers. Some of those who refused were subjected to administrative disciplinary action and administrative separation, while others were prosecuted at court-martial. At the same time, federal courts were deciding that the program was not lawful and that informed consent was required. Circumstances changed when the FDA removed the experimental status of the vaccine.

So what could happen if mandatory COVID-19 vaccinations are ordered?

Every military lawyer (and service member) knows that all orders are presumed lawful and that a person disobeys "at their peril." Disobedience of a lawful order is a criminal offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. That said, are there any defenses to such disobedience that can be raised at a court-martial? The answer, based on the anthrax precedent, is likely no. If there are any defenses, they would be grounded in a medical or religious exemption.

In the 2012 case of United States v. Mixon, a Marine deploying to Afghanistan refused anthrax and smallpox shots for religious reasons. (The case notes that he had "numerous other immunizations earlier in his career, including Hepatitis A and B, influenza, pneumococcal, polio, yellow fever, tetanus-diphtheria, measles, mumps, rubella booster and meningococcal.) We don't know if his defense would have worked for him because he pleaded guilty to the disobedience and, along with convictions for other offenses, his sentence included three months in the brig and a bad conduct discharge.

How would Chance Mixon have fared had he not waived the defense and were his trial heard today -- at a time when the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, or RFRA, is in place? U.S. v. Sterling, a recent military law precedent, provides some clues.

First, a "religious exercise triggers the RFRA inquiry." Refusal to take a vaccine for religious reasons almost certainly would count since that concept includes "abstention from … physical acts … for religious reasons."

Next, a court would ask whether the lawful order "substantially burdened" a "sincerely held" religious belief.

Finally, the sincerity inquiry will probe your motives: Is your refusal really based on your religion, or is it something you read online? This is highly specific to you.

But what about "substantial burden"? This part of the analysis asks whether the order burdens an "important" practice of the religion, such as violating a tenet of the faith. The Sterling court held that service members would not be "substantially burdened" as a legal matter unless they first request accommodation through their command and that accommodation is denied. (This denial is likely in the COVID vaccine context.) Again, the decision will depend on your individual circumstances. You will need to show that an important part of your religion was burdened by taking the vaccine.

But even if someone makes it past these hurdles, they still can be punished for violating the order if the substantial burden on their religious exercise is "the least restrictive means of furthering a compelling government interest." No court is likely to hold that ending the COVID-19 pandemic does not constitute a compelling interest, but what about the first question? Is a vaccine the least restrictive means of ending the pandemic? This would also be a fertile area of litigation, where the service member would need to show that other measures -- say, masks, distancing, or working from home -- are workable solutions.

Service members should be aware of regulations and policy in place that allows them to first seek an exemption on medical or religious grounds. Failure to use the exemption request process is part of the reason Monifa Sterling got in trouble.

-- The opinions expressed in this op-ed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Military.com. If you would like to submit your own commentary, please send your article to opinions@military.com for consideration.