Decades before Tom Clancy wrote “The Hunt for Red October,” an Italian naval officer pulled off a stunt that could have come straight from a Cold War spy novel — he stole a submarine to spark a war.

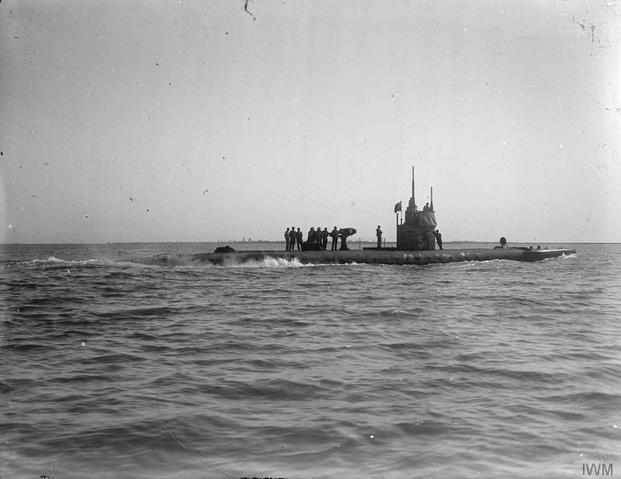

On Oct. 3-4, 1914, Lt. Angelo Belloni seized control of submarine F-43 at the Muggiano shipyards near La Spezia, Italy. The coastal submarine, originally built for the Russian Navy and designated to become the Svyatoi Georgjy, never made it to its intended customer.

Belloni convinced about 15 sailors under his command that they were embarking on a secret mission. They believed him. His actual plan was far more audacious: attack Austro-Hungarian warships in the Adriatic Sea to force Italy into World War I.

Though initially allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary, Italy chose to remain neutral in the early months of the war, citing that they were only allied defensively, and Austria-Hungary had been the aggressor. This neutrality frustrated interventionists like Belloni, though he and many other Italians felt the Austro-Hungarians were the true enemies of Italy.

Rather than wait for diplomats to decide his country's fate, he took matters into his own hands.

A Rogue Italian Officer Steals a Submarine

After stealing the submarine, Belloni sailed the vessel to Corsica, hoping to secure French support for his mission. He needed torpedoes and political backing from France, which had already entered the war against the Central Powers. Meanwhile, French and British diplomats were working tirelessly to persuade Italy to join their alliance.

Italian officials quickly noticed their submarine was missing and sent out naval patrols to find the vessel. Belloni managed to avoid numerous Italian destroyers; while hoping to find an Allied ship willing to rearm the submarine so it could complete its mission. They never encountered any. The secrecy of his plan and the complications faced by the patrol caused the crew to become suspicious of their commander’s intentions.

Upon reaching Corsica, the crew attempted to enter Ajaccio harbor where French troops almost fired upon the ship, mistaking it for a German U-Boat. French officials, after hearing Belloni's proposal, declined to support what amounted to an act of piracy and refused to be implicit in the plot. The crew by this point realized they had been tricked and opted to cooperate with the authorities, despite Belloni’s objections and threats.

The French then informed the Italian authorities of the incident as French troops seized the vessel.

The submarine returned to Italy without Belloni, who remained in Corsica for two months before facing trial on charges of submarine theft and 12 other offenses. Under normal circumstances, he would have been convicted and likely executed. But Italy's entry into the war in May 1915 changed everything. Military judges acquitted him, recognizing both his patriotic motives and his technical expertise.

The Royal Italian Navy quickly brought Belloni back into service. The submarine he stole was requisitioned from Russia and renamed Argonauta, serving the Italian Navy during the war.

The Real Stories Behind “The Hunt for Red October”

The parallels between Belloni’s plan with Tom Clancy’s novel, “The Hunt for Red October,” are striking. Both stories feature a naval officer commandeering a submarine while convincing the crew they're on a legitimate mission. Both involve attempts to trigger major geopolitical changes.

But Clancy's 1984 novel drew its inspiration from different sources entirely. According to The National Interest, two real Cold War incidents shaped the book: the 1975 mutiny aboard Soviet frigate Storozhevoy and the mysterious 1968 sinking of Soviet submarine K-129.

Soviet Captain Valery Sablin seized the Storozhevoy in November 1975, attempting to spark a revolution against Soviet corruption. Unlike Belloni's scheme to bring his country into conflict, Sablin sought internal reform for his nation. Soviet forces bombed and disabled his ship before he could reach Leningrad. He was executed in August 1976.

The K-129 incident remains a secretive topic. The submarine sank in the Pacific in 1968 under unexplained circumstances, before later becoming the target of a secret CIA recovery operation. The government managed to recover the ship and several vital intelligence items, though they still have not disclosed what exactly was recovered.

For his novel, Clancy merged the two incidents into a plot revolving around a Soviet submarine commander tricking his crew into surrendering their vessel to American authorities as the Soviet navy pursues them. Interestingly similar to Belloni’s mission.

Naval Mutiny for Strategic Change

While it was not one of Clancy’s direct influences for his novel, Belloni's 1914 covert mission reveals how a single man on a determined path can alter entire strategic outcomes. The Italian officer's theft of an entire submarine predated the Cold War incidents that did inspire Clancy by six decades, but shows that history often repeats itself.

What separates these stories is outcome. Belloni eventually received vindication and continued his naval career, later becoming a pioneer in diving technology which helped establish Italy's famed Xª Flottiglia MAS that later caused massive damage to the Allies during WWII. Sablin faced a firing squad for his mutiny.

Both men believed the ends justified extraordinary means — seizing control of warships to trigger change larger than themselves. Military courts judged them both differently, but their willingness to commandeer naval vessels for their causes connects them across 60 years of military history. These real-life incidents prove that naval officers risking everything for their convictions makes compelling drama whether it happens in 1914, 1975, or on the pages of a Cold War novel.